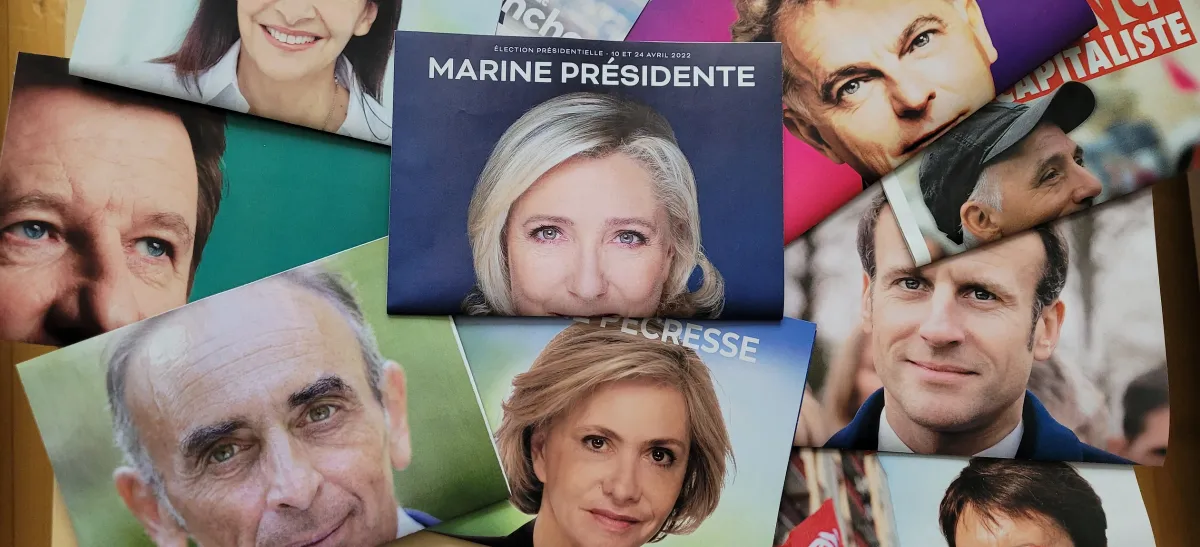

France Is Endangering Its Democracy by Letting Two Far-Right Candidates Run For Its Presidential Elections: How Did It Get There?

The first round of the French presidential elections will unfold this weekend, and the country's political landscape has never been more alarming.

Access the Audio Read version of this article directly on Spotify for Podcasters.

"Far away in the polls despite an awkward campaign, Macron knows that he can benefit from this “beaver” voting movement if Le Pen joins him in the second round, and that he wouldn’t need to particularly defend the lukewarm outcome of his term."

A few days ago, French president Emmanuel Macron recognised, during an interview on French radio France Inter, that he “failed to restrain” the rise of far-right movements in the country. His admission, expressed without any form of regret, highlights France’s ambivalent position when it comes to the far right.

While the first round of the presidential elections will unfold on this very Sunday, the country's political landscape has never been more alarming. Currently, five candidates are considered by the polls as best placed in the run for office. But despite this apparent opening, two of them represent right-wing extremism: Marine Le Pen and Eric Zemmour.

The first may be a familiar name to those who regularly follow French politics. Since 2011, Marine Le Pen has been the main figure of the Rassemblement National (RN), the country’s historical far-right party founded by her father, Jean-Marie Le Pen - albeit rebranded from the Front National - condemned several times for Holocaust denial and hate speech. Throughout the years, she has installed herself as a serious political threat and just like 5 years ago, she is even predicted to go through the first round of the elections to face Emmanuel Macron in the second (and last).

On the other hand, Eric Zemmour is completely novice in politics, but has been a familiar face on French TV for almost two decades - another ‘politainer’ in the wake of Donald Trump. The controversial commentator, known for his xenophobic and Islamophobic views, has been condemned for hate speech on multiple occasions just like Le Pen’s father. His abundant misogynistic and retrograde opinions are also regularly pointed out in the French press and social media, with one famous line stating that “the man is a civilised sexual predator”. Zemmour is also accused of several accounts of inappropriate behaviour and sexual assaults.

Zemmour, who is currently stagnating at the fourth place in the polls, is often qualified as Le Pen’s “idiot utile” (or ‘useful idiot’), a term often used by observers to describe his role in her instalment as a legitimate candidate. His choice to run a Trump-like campaign with direct attacks against those who he feels are provoking “France’s decline” (as covered in his book The French Suicide) ‘almost’ gives the impression that Le Pen views are moderate.

According to Zemmour, “LGBT, but also anti-racist activists are coming in schools and indoctrinating children” (Source: Brut). Meanwhile, Marine Le Pen states that “no sexuality should be promoted to minors. They should be left alone”. She also specifies that she is “opposed to all discriminations”. It is clear that the words they both use don’t carry the same weight, an unexpected help for Le Pen’s ‘de-demonising' strategy of the party, which she has been coordinating for the past ten years. Here, Le Pen could ‘almost’ appear as an “ally” if it wasn’t for her comments on gay rights not being “respected in numerous no-go zones areas in France”, another denial of France’s global, and not specific to some targeted communities, problem with LGBTphobia (Source: Euronews).

But why is France tolerating such candidates for its most important elections?

There is a first short and pragmatic answer: their presence is an electoral advantage. In 2017, when Le Pen reached the second round, the majority of the political class called for a “Republican dam” to prevent her from winning. In the collective psyche, the far-right still constitutes a danger for democracy: the ghost of France’s authoritarian and Nazi Germany-friendly regime during the Second World War stays present.

Far away in the polls despite an awkward campaign, Macron knows that he can benefit from this “beaver” voting movement if Le Pen joins him in the second round, and that he wouldn’t need to particularly defend the lukewarm outcome of his term. Zemmour may reinforce Le Pen as a serious candidate with his countless controversies, but Macron places himself as a protector of the country from Le Pen’s softened version of far-right ideology. However, this tolerance of ultra-intolerant parties says a lot about France’s relation with freedom of speech, because if the far-right represents such a huge danger for democracy, why on earth has their agenda been pushed throughout the whole campaign with little to no consequences?

A few months ago, when Le Pen and Zemmour struggled to obtain the 500 needed signatures from elected officials (or ‘sponsorships’) to launch their candidacy, some of their political opponents actually called for a “democratic mobilisation” to help them. The justification was that every current of opinion should be represented.

François Bayrou, the politician who initiated this sponsorship boost, said he was certain that by allowing the candidacy of everyone, “even of those [the country] most fight”, the democracy would be protected (Source: 20 Minutes).

What was the result of this help? A campaign that hyper-focused on the “great replacement”, a white supremacist conspiracy theory which notably contributed to the Christchurch massacre in 2019 (Source: Info Migrants). This theory appeared at the end of the 19th century, and spoke about a new population that would take over, triumph and "ruin our homeland" - at the time, French nationalism founder Maurice Barrès was referring to Jewish people.

With the rising number of anti-Semitic and Islamophobic acts, racist assaults, and anti-LGBT attacks, and with the difficult fight against structural gender discrimination in a country still plagued by feminicides, should France really continue this dangerous political game?

As a Black woman living in France, I’ve already seen some of the effects of these far-right ideas with my own eyes. From the racial abuse I used to barely experience in public, to the difficulty to express so-called “radical” anti-racist and pro-LGBT views without being negatively labelled as “woke” in a derogatory way, the atmosphere is heavy for me.

To be honest, I don’t even feel safe anymore. My hometown, Lyon, is more and more targeted by white nationalists, with recurrent fights at football games, nazi signs and daily reports of racist insults towards Black shop owners. I can’t even imagine what this maintained impunity for those who spread hatred and encourage violence will trigger in the following years.

I remember my dad always telling me that when I get older, I’ll come to the same conclusion as him: nothing changes in France, because defending the right of minorities to peacefully exist is always considered as less pressing than defending those who have always oppressed them.

In the “The Open Society and Its Enemies” (1945), Karl Popper wrote that “if we extend unlimited tolerance even to those who are intolerant, if we are not prepared to defend a tolerant society against the onslaught of the intolerant, then the tolerant will be destroyed, and tolerance with them”. I’m just not too sure France is ready to face the potential long-term consequences of the total normalisation of hateful speeches and divisive discourses.