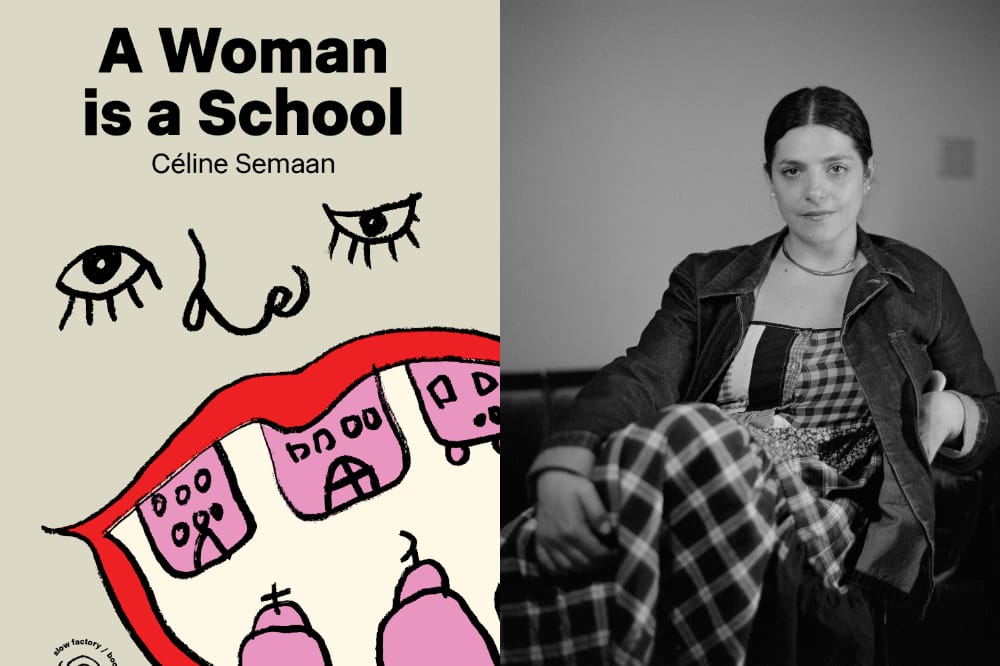

When Storytelling Becomes Resistance: Céline Semaan on 'A Woman is a School'

Céline Semaan challenges us to rethink everything we’ve been taught to aspire to: fashion, education, even the idea of womanhood itself.

This article marks the start of a series exploring Resistance as a Force for Change - in partnership with intersection, a borderless network visibilising people working on the frontlines of climate, social and racial justice. Through interviews and insight-led pieces, we examine how marginalised voices navigate, and challenge, systems of power. They are not just about survival, but about the radical act of imagining something better. They reflect the complexity of what it means to resist: the weight of history, the imprint of culture, and the structural forces that shape our lives. Real change begins when we reckon with these truths, and choose to build from them.

Access the Audio Read version directly on Spotify for Creators.

At the intersection of climate, culture, and human rights, stands Céline Semaan, co-founder of the environmental and social justice non-profit Slow Factory, and media, Everything is Political. Her debut book, "A Woman is a School," is not a typical memoir, it is an exploration of decolonial storytelling, cultural preservation, and resistance, rooted in the lived experiences of a war-survivor and child refugee from Lebanon. Drawing on the ancient storytelling tradition of the Levant, the "hakawati", Semaan documents decades of history, knowledge, and wisdom often endangered or discredited, particularly from the Global South.

It's a fairly warm Tuesday evening in April in Paris and I'm heading to a cafe in central Paris to attend a talk with Céline Semaan, author of A Woman is a School, moderated by fashion journalist and author Mélody Thomas, as part of Semaan's book tour.

Céline Semaan positions herself as a modern hakawati in her book - the Arabic version of a storyteller. The book is a deliberate act of cultural preservation, memory, and resistance, drawing deeply from the storytelling traditions of her region.

With this book, Semaan explicitly resists the expectations of the Western publishing industry, which often demands linear, "uplifting" narratives from refugees. She wants to be in charge, and lead with heart and not $$$. She critiques the prevalent "refugee success" trope, stating that her book is not about a war survivor who "made it in the world". Instead, it's a deeply personal, non-pedagogic account rooted in lived experience, cultural memory, and the endangered knowledge taught by elders. By insisting on writing from her own gaze and for her own people, rather than catering to a perceived "white gaze," Semaan reclaims agency over her story and challenges the colonial structures inherent in mainstream publishing.

The unique format of "A Woman is a School" reflects the fragmented nature of memory and displacement. Something that as a daughter of immigrants somehow feels familiar. The book is structured into non-linear chapters, each inspired by cassette tapes. During times of displacement, cassette tapes were a vital medium for carrying family memories and emotions, serving as a primary form of communication across borders before the internet.

Semaan describes how her parents would listen to these tapes, crying privately before asking their children to record something in return. This experience shapes the book's structure, where each chapter functions as a standalone yet interlinked "sonic memory". This format is not just aesthetic, it mirrors the fractured memories and fragmented communication experienced by displaced families.

The very title, "A Woman is a School," begins with a decolonial and inclusive definition of womanhood. Semaan explicitly rejects gender binaries, framing them as constructs imposed under patriarchal colonial rule - a concept echoed in various readings, and covered by writer and performance artist Alok Vaid-Menon in 'Beyond the Gender Binary'. Semaan's definition embraces anyone who identifies as a woman, regardless of nation-state definitions or limitations based on gender norms.

The concept of "School" in the title is expansive, encompassing not just mothers, but also sisters, aunties, friends, and even Planet Earth as teachers; asserting that all gender norms are creations of colonisation. A central theme is the critique of the education system as a tool of colonialism. Semaan uses the metaphor of colonialism as a spider with tentacles reaching into education, media, fashion, and science. She argues that institutional education promotes a white gaze, Western superiority, and an incomplete version of history.

Semaan challenges the internalised belief that colonisers brought civilisation, asserting that her people - Indigenous people of her land and beyond - were literate before colonisation. Therefore, a key concept is the necessity of lifelong unlearning to dismantle colonial myths and challenge internalised colonial thinking that shapes our ideas of success, culture, and education against our own traditional knowledge.

Semaan recounts the painful experience of being "othered" both in exile in Montreal, where she was referred to solely by her origin ("Lali Vanessa”, “the Lebanese girl"), and upon returning to Lebanon, where her identity was questioned due to her broken Arabic. This highlights the complex reality of displacement, where one can feel like an outsider everywhere.

The book becomes a "witness act," per her words, where readers become memory-bearers of the displaced experience. Semaan reclaims her role as a "cultural translator," someone who explains where she comes from. She draws on the Arabic word Shaheed, meaning both martyr and witness, emphasising the importance of bearing witness to carry stories. By refusing to write for the "white gaze," she insists on centering the stories and experiences of her own people.

The challenges Semaan faced with publishers underscore the ingrained colonial biases within the industry. Being told she talked "too much about colonisation" and would make white readers "feel bad" reveals a demand for narratives that do not challenge or discomfort the dominant perspective, and continue to comfort marginalised voices into what they want them to remain, marginalised.

Semaan powerfully rejects being framed solely as a victim or an "inspiring" success story. She asserts the inherent agency and dignity of oppressed peoples, stating,

"We are not victims. Even though we have been victimised, we continue to have agency, to have dignity".

She speaks of the insistence on being human, finding joy, and dancing under bombs as acts of resistance. This refusal to dilute her message or cater to fragile sensibilities is a direct challenge to the colonial gaze in the media.

Shifting to the realm of material culture, Semaan identifies fashion as another "arm of colonialism". Fashion dictates standards of professionalism, beauty, and elegance, often devaluing traditional dress in favour of European styles. It controls social status and visibility, defining who is seen as successful and aspirational, often aligning with a "colonial status" or placing the "white man at the top of that triangle".

Examples include natural hair often not being considered professional attire, a residue of colonial beauty standards. Semaan notes how "aspirational fashion" is frequently connected to colonial power structures. Wearing traditional attire, in this context, becomes a radical act of visibility and resistance.

Semaan is also precise with language, particularly regarding the term "decolonising." She avoids using "decolonising fashion" lightly, stressing that for her, decolonisation is specifically about "land back" and sovereignty, not merely a metaphor for aesthetics.

These terms echo past conversations, such as this previous interview with Aja Barber, and others talks I attended this year, highlighting the quiet rise and need for more accuracy in our language, our history and how they impact our behaviour and system today.

Instead, she advocates for "decentralising fashion". This involves the "hard labour" of shifting the industry away from the white/Western gaze and its associated power structures. This decentralisation allows for fashion to be used as a tool to reclaim identity, challenge imposed norms, and resist internalised colonial values. Semaan observes that despite efforts post-2020 to bring more diverse bodies into the mainstream, there has been a significant regression, with the rise of '90s-style beauty ideals (skinny models, "trad wives") and trends like Ozempic, which she sees as manifestations of control over the public and bodies.

Slow Factory and Collective Liberation

"A Woman is a School" is listed among Slow Factory's "Books for Collective Liberation," placing it within the broader work of the organisation. Slow Factory is described as an environmental and social justice non-profit that works at the intersections of climate and culture to build partnerships and communities. Its mission is to redesign harmful systems and empower people of the Global Majority through educational programming, regenerative design, and materials innovation, aiming for what is good for both the Earth and people.

Semaan also leads "Designing Possible Futures" classes through Slow Factory, covering topics such as Resilient Design, Radical Healing as Justice Work, Building International Solidarity, Decentralized Design Practice, and Lifelong Unlearning. These classes are tied to her book tour events, providing a space for deeper engagement with the book's themes and actionable frameworks for change.

Through her book and the work of Slow Factory and ‘Everything is Political, Céline Semaan offers a powerful voice challenging colonial structures and advocating for systemic change grounded in lived experience, Indigenous knowledge, and collective liberation. Her work encourages a critical examination of inherited systems, from publishing and education to fashion and gender norms, and calls for a "re-indigenising" of our relationship to the world.

Explore Slow Factory and order your copy of a Woman is a School.

intersection is a borderless network visibilising people working on the frontlines of climate, social and racial justice. To find out more about its work, mission, and become a member, visit https://intersection-network.carrd.co/.